A TOUR IN THE CALTON.

By Peter Fyfe. Read 15th February, 1917.

Many will remember the dens of squalor and disease which were cleared out in the Bridgegate and the Wynd under the Act of 1866 ; and again, under the Act of 1897, how the tumble-down and rickety tenements on both sides of the High Street and those situated in the Rottenrow were removed. The time of the Calton, with its irregular streets and decayed tenements, is coming.

Meantime it is an interesting spot, dotted over with landmarks of historic interest, places where splendid human endeavour is at work to uplift the race and a work-a-day life exists which is not to be found in any other section of the city. Let me give you first of all some conception of the area and a few statistical details regarding this ward which mark it as one which must, as early as is practicable, have the attention of the Corporation Special Committee on Housing.

Its western boundary is the shortest, extending from Glasgow Cross down Saltmarket Street to the Clyde. Southward it follows the serpentine course of the river, until we reach the bridge at the foot of Main Street, Bridgeton ; thence, on its eastern side, it runs up the centre of Main Street to Bridgeton Cross, along Canning Street, until we come to Abercromby Street (formerly Clyde Street), and up the centre of that street until Gallowgate is reached. From this point along Gallowgate, back to Glasgow Cross, forms its northern extremity.

The whole area extends to 327 acres, containing about 7,580 houses and 34,520 people. The land density of Calton is thus not an extreme one, being 106 persons on each acre, but this can hardly be considered a true density, as this ward has within it the whole of Glasgow Green on its southern side. The house density is 4-55, that is, there are fully four adults and one child, or this equivalent, in each house on the average. The general death-rate is a high one for modern times, averaging during the eleven years from 1903 to 1913, 21.53 per 1,000 of its population, as against 17.04 for the old city before annexation for the same eleven years.

The infantile mortality rate in any area, which may reasonably be considered extensive and populous, is generally recognised to be a sensitive index to its place in the vital statistics of a city or a nation. Infants under one year are peculiarly sensitive to unhealthy environments and economic pressure, and these two are, in towns, always in association.

Taking from the statistical records the infantile mortality of this ward for the eighteen years ending 1913, I find that, on the average, 164-3 babies die out of every 1,000 born, before they see their second birthday. No ward has such a bad infantile record but Cowcaddens. The average for the old city during this period was 132.3 per 1,000, or thirty-two per 1,000 less. There can be little doubt that poverty and Ignorance have the major responsibility for this dreadful condition of affairs. I find that fully a thousand infants are born in the Calton every year, and that only 28 per cent. of the mothers have any medical attendance given to them. Such facts have a special significance at this period of Great Britain's history. I will take the liberty, if time permits, to refer to this aspect of our national problem after I have taken you through the tour which I, along with Inspectors Strobridge and Roy, made of this historical ward.

Before starting on our journey, allow me to show what this area was like in 1760, as sketched by an artist of the period. The whole district south of the Gallowgate and east of the “Cross was then known as " Barrowfield," or Burrelfield "—probably meaning, as Dr. Renwick has noted, arable country devoted to agricultural purposes, and laid out in burrel " or barrel-shaped ridges. The portion of this land which lay nearest to Glasgow was known as Blackfauld," or land blackened by surface coal workings, which were common during the early years of the eighteenth century.

In 1725 the Calton had become, relatively for that period, a populous suburb, and its weavers and cordiners were beginning to compete in trade with the privileged Trades Incorporations of its big neighbour on the west. Free Trade was not understood in these days, or, at all events, was by no means appreciated; so conferences had to be held and agreements come to as to restricting their trading propensities.

It was not until the year 1817 that the villages of Old and New Calton were, by a charter granted by George Ill., formed into a burgh of barony, with a provost, magistrates, and police of its own. It is not my purpose to enter upon the early struggles of the burgh to form itself into a well-governed unit. A good description of these, and generally of the burgh's independent life, until it was absorbed by Glasgow in 1846, will be found in Dr. Renwick's illuminating papers to the Regality Club, volume IV. It is in the Calton of to-day I am more particularly desirous to interest you. Its rural aspect has gone, never to return. The leafy shade under which lovers of the olden time used to wander as they strolled along the banks of the Camlachie Burn, within easy night and sound of Saint Andrew's Kirk, has given place to huge erections of stone and lime; the delightful burn, with its eager anglers on either bank, is a filthy sewer ; and the green lanes and quiet byways through the meadows, are ringing from morning to night with the traffic of the Second City of the Empire.

As we stand at the most western point of the ward in Saltmarket Street, and observe the ever onward rush of life, —north, south, and west—and think of what has been accomplished in this city of ours since she absorbed the burgh of Calton in 1846, we are seized with some of Alexander Smith's civic pride, expressed in the lines: “All raptures of this mortal breath, Solemnities of life and death, Dwell in thy noise alone: Of me thou hast become a part— Some kindred with my human heart Lives in thy streets of stone."

What Glasgow citizen has not the experience of a rapture such as this, as he gazes down the renovated dear old “Sautie”?

It is enhanced as he stands in St. Andrew's Street, opposite the well-known "family home," and looks westwards towards that building across Saltmarket, where in 1763 the world-famous James Watt married his cousin and first love, Miss Miller. We seem to see the spirit of him whom Sir Walter Scott described as "the alert, kind, benevolent old man," in the steam-road locomotive which rumbles past us, laden with merchandise, and in the locomotive overhead as it thunders past towards Saint Enoch's.

The "home," with its 160 bedrooms, rented by the Corporation at 5s. 6d. per week to men with motherless children, stands in no need of description. It is a pity there are not more of such creches in the city, where the young children of those who, by circumstances, are compelled to labour from six in the morning till six at night, may be left by them, in the assured hope that they will be well looked after during their absence.

A few steps brings us face to face with St. Andrew's Church, completed in 1756, at a cost to the city of over {20,000. It, and particularly the episcopal Church, farther south, earned at that time considerable notoriety as the "Whistling Kirk," as the public believed (erroneously) that the small two-stop organ made by James Watt was being played at the Sunday services in 1807. Galt, in his well-known work, entitled "The Entail," makes one of his characters enlarge upon this alleged Sabbath desecration in St. Andrew's, where, in a conversation with Mr. Walkinshaw, Cornie, the elder, breaks out into a diatribe on "carnal innovations on the speerit o' the Kirk of Scotland," winding up thus, “Mister Walkinshaw, am nae prophet, as ye will ken, but I can see that the day's no far aff, when meenisters of the Gospel in Glasgow will be seen chambering and wantoning to the sound o' the kist fu' o' whustles, wi' the seven-headed beast routing into choruses at every o'ercome o' the spring."

The interior of St. Andrew's conforms with the massiveness and dignity of its exterior. We feel, as we step inside, the meaning or Milton's lines in "Il Penseroso

" The storied windows richly dight,

Casting a dim religious light. "

In days gone by the Church was surrounded by the homes of Glasgow's prosperous citizens, the houses being of large capacity, three and four storeys in height.

Passing round it by the north side we note Quarrier's City Orphans' Home, and recall the self-denying labours of him whose name is associated with this place, and with that other and better-known institution, or rather manifold series of institutions, at Bridge-of-Weir, for the rescue and proper training of the young. It is to be hoped that at no distant time Glasgow will, in some appropriate and marked manner, raise a suitable memorial to the man who gave the best years of his life to the noblest purpose to which any human soul can devote its efforts. He, inspired by the example of his great Master, had engraved on the tablets of his heart the Divine words : Suffer little children to come unto Me. "

At the other end of the square, on the north side, the large houses of the gentry of a hundred years ago have been converted into common lodging-houses for women of a very low class. A view of the interior of these is one of the sad sights in every large city. As I wrote some years ago in respect of the farmed-out houses in Glasgow, after a midnight visit to some of these, there appears to the ordinary observer to be written over these lodging-houses the words which Dante saw flaming over the Gate of Dis in the infernal regions :

“All hope abandon ye who enter here." I entered there and chatted with a number of the women, some cooking their meagre breakfasts, others cleaning up their apartments, one or two just out of bed, adjusting their poor tawdry raiment —all, or nearly all, Magdalenes of the very humblest type.

A polite question or inquiry invariably brought an equally polite answer; and, notwithstanding the sinister and downcast appearance of many of those I addressed, I came away with the impression that to be hopeless, even with regard to these, the very residue of our "submerged tenth," was a blunder. Enmeshed as they are in ignorance and want, and surrounded on all sides by the temptations of the "wee pawn” and the public-house, it is not to be wondered at that, having fallen, most of them fail to rise again, but it is a well-established fact that some do rise.

Just a stone's-throw from this place on our way down Low Green Street, we observe in Steel Street that great " hospital for souls," known as "The Tent Hall"—a monument in stone and lime to the Christian endeavours of the United Evangelistic Association of Glasgow. Here, and at their “Bethany Hall" in Bridgeton, the association carry on their labours of rescue, not only of human " broken earthenware," but also of adolescents and children. The band of noble citizens who carry on the work of going out into the lanes and slums of our city seeking to save, have thirty-eight years of a splendid effort behind them. They are quite conscious that among the thousands who frequent this place every Sabbath morning, a large proportion are undeserving, and, like the multitudes which followed the Master himself in Palestine, are there for the sake of the loaves and fishes; but this does not deter them, because they have good evidence that about a fourth of those who come expressing anxiety for a better way of life are restored to good citizenship. To read the yearly report of this association is to realise that over no man or woman should the awful words I have quoted from Dante ever be inscribed. Even as to our poor waifs in the common lodging-houses, it may be predicted, given sincere human effort, that wherever there is life there is hope.

Turning into Greendyke Street, we pass at the corner the old episcopal Church of St. Andrews, showing plainly the ravages of time, assisted by want of repair. It was the first church of its kind to be built in Scotland after the Revolution, and it was to it, and not really to St. Andrew's Parish Church, that the contemptuous epithet of the ' Whistlin' Kirk " was applied. It may be that in these years, which followed closely upon the heels of the Revolution In our country, religious prejudices and bigotry had not had time to die, and that the pronouncement of the Earl of Chatham that the Church of England had a Popish liturgy, a Calvinistic creed, and an Armenian clergy had some truth in it ; yet it is humiliating as we look upon this decaying edifice, to remember that its erection involved the builder, Andrew Hunter, in the bann of excommunication from his own church of Greyfriars.

Possibly our ancestors of that period had put too liberal an interpretation upon Defoe's lines, written earlier in that century—

" Wherever God erects a house of prayer,

The devil always builds a chapel there ; And 'twill be found, upon examination,

The latter has the largest congregation. "

Of all the civic enterprises of the Glasgow Corporation, perhaps there is none which shows such a marked desire to meet the needs of the poorer part of her population than the Old Clothes Market in Greendyke Street, Calton. We are all more or less familiar with Dickens's description of Krook's rag and bottle warehouse in "Bleak House." We have several of these unsavoury "stores" scattered over our teeming city, but here we have a roofed and galleried emporium covering over 2,300 square yards, leased out in stalls or stances to dealers in second-hand and worn clothing of every description. Eighty leaseholders, renting their stances at from 2s. 6d. to 12s. per week, exhibit their wares, rescued from the " devil " or laniary machine of the flock factory. Where these are collected and whence brought to this place is one of the mysteries of the underworld of the city. Busy human "ants" may be observed now and again scurrying out of closes with huge bundles on their backs, and, if followed, may be seen picking out the usable from the unusable, the woollen from the cotton, and generally classifying their wares for sale. Catching the “crumbs which fall from the rich man's table," they are the waste-preventers of the city, and thus not only serve themselves with a humble living, but help others, equally poor, to be served with still serviceable articles of clothing. Some of these " collectors," like those in higher walks of life, occasionally seek to make a " corner in such material. To secure a big stock " and wait for the rise " is the game of some rag-pickers as well as of market manipulators. One of them filled her two-apartment house four to five feet deep with rags and cast-off clothing, till Mr. Waddell and his fire brigade found her in flames one night, quenched her rags and her miserly ardour with cold water, and covered the back-court with the accumulation of years. When I saw her, she was wandering disconsolate and forlorn among the residue and groaning inwardly over the evil fate which had overtaken her. Entry could never be obtained to her house, as knocking at her door gained no response. Even the house factor had never seen inside of it, as he informed me, she was invariably prompt with the monthly rent, which she paid personally at his office two or three days before it was due. To such lengths do some go that their exercise of the virtue of thrift or the sin of cupidity brings them within the borderland of crime.

We are reminded as we pass along to Charlotte Street of the gigantic struggle for freedom and civilization which, in association with comrades drawn from every spot in our far flung empire, our gallant lads of the 9th Highland Light Infantry are carrying on in the battlefields of Europe. It was on behalf of this now famous regiment that the first of the Sanitary Department were made. So great and immediate were their demands for sleeping space that, before echoes of Britain's war declaration had died on the air, we had cleared out the Old Clothes Market, and sprayed out every nook and corner of that great building with a powerful disinfectant, thus preparing a clean and healthful place of sleep for our local Highlanders. The deeds of Scottish valour have yet to be written fully in the annals of the most stupendous fight for righteousness the world has ever beheld, but we may be sure that those who learned the art of war in this building, and hardened their muscles by vigorous exercise on the Calton Green, will be found occupying a place of honour second to none, when the history appears.

One of the many barracks of a different kind of army meets our view as we wend our way up Charlotte Street. In the spiritual and moral struggles against the inroads of human weakness and vice, the Salvation Army have for many years taken a most active and honourable part. That they should have landed here in the old historrc house of David Dale, one of Glasgow's great merchants and philanthropists, is of happy omen. If the spirit of David Dale, the whilom herd laddie and weaver's apprentice of Paisley, and later the father of Glasgow's reat cotton industry (now practically centred in Lancashire were to revisit the glimpses of the moon, and see his great mansion converted into a centre of rescue for human souls, we can well imagine it whispering a ghostly blessing over it, and expressing ' the thought of Emerson's lines in " The Problem

" Myself from God I could not free ;

I builded better than I knew."

As we wend our way towards London Street we bear in memory that in this short street Professor John Stuart Blackie was born, and that, for a time, one of Scotland's greatest poets, Thomas Campbell, resided in it. At this dread hour of Poland's eventful history, it is fitting to remember what this Scottish genius did in 1831 for this unfortunate and down-trodden race, and the recollection of his deep distress and plentiful tears over her unhappy fate, should be to his countrymen of to-day an inspiration and a guide to our dealings with the barbaric empire which at present holds her under duress.

We are now on a small part of the road which our forefathers intended should lead directly from the second to the first city in the empire. The stage-coaches which, before the days of railways, ran regularly between London and Glasgow, had their halting place at the Saracen Head Inn in Gallowgate, but the cutting asunder of Charlotte Lane or Balaam's Pass and the forming of this new street was sought at this period (1824) to be a fitting opportunity to make a grand boulevard in front of Monteith Row, through the Greenhead to London Road, instead of following the tortuous course by way of Great Hamilton Street and Canning Street. Vested interests, as usual, opposed the scheme; and just then George Stephenson was at work upon his attempt to apply the steam locomotive on his 38-mile single track between Stockton and Darlington. The strong support thus given to the opposition for the making of the new stage-coach road, caused it to be abandoned, and we are left with the narrow pass or lane I have mentioned as our straightest route from this point to the heart of the empire. It is to be hoped that some citizen of note and outstanding love for St. Mungo may take it into his head to abolish this " pass " and the congeries of hideous buildings which lie to the south of it, and make a children's playground where these shanties now " cumber the earth."

Through Balaam's Pass we emerge upon Great Hamilton Street. On our left, at the corner, was the site of the oldest tavern in the city, known as " The Burnt Barns," established in 1679. To-day it is an ordinary 'c pub." beneath a fourstorey tenement. Unlike the old one, it bears no appearance of romance. It is Boswell who records of Samuel Johnson that he expressed the opinion that " there is nothing which has yet been contrived by man, by which so much happiness is produced as by a good tavern or inn." Doubtless when these centres of social intercourse and refreshment were so spaced that it took the traveller a good walk to gain access to the next one on his journey, something might be said in favour of the good doctor's view ; but a " pub. " at practically every corner is a different matter. In Calton Ward there are 88 public-houses, or one for about every 100 householders, which, as they all seem to flourish, argues no mean capacity on the part of the inhabitants for imbibing such " happiness as publicans have to bestow.

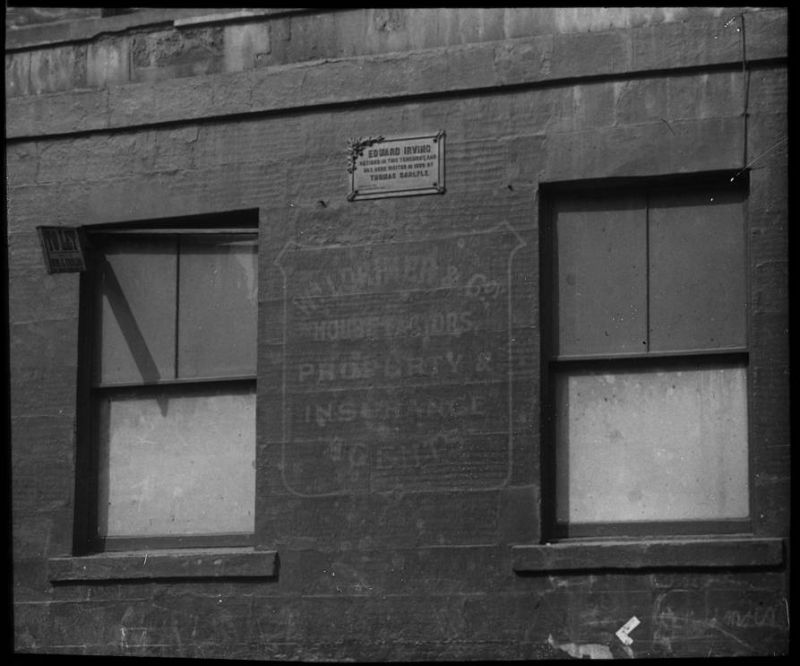

Passing down Kent Street, the eye is arrested at No. 34 by a small tablet affixed between two windows of a house at the corner of Suffolk Street. It is the house which was occupied by him whom Carlyle termed " Scotland's Herculean Man "—Edward Irving. The much revered pastor of St. John's, Dr. Thomas Chalmers, was the means of bringing Irving to the city as his assistant and missionary in the parish in 1819. He is thus described by a biographer—" His commanding stature, the admirable symmetry of his form, the dark and melancholy beauty of his countenance produced an imposing impression, even before his deep and powerful voice had given utterance to its unmelodious thunders." This was the being who inhabited this living room and kitchen house, until he was ordained minister of the Caledonian Church in Hatton Garden, London, in 1822. Carlyle, his close friend and admirer, writing of his death at tlie age of forty-two, says of him—"By a fatal chance, fashion cast her eye on him, as on some impersonation of novel-Cameronianism, some wild product of nature from the wild mountains. Fashion crowded round him, with her meteor lights and Bacchic dances; breathed her foul incense on him, intoxicating, poisoning! Our mad Babylon wore him and wasted him, with all her engines, and it took her twelve years. He sleeps with his fathers, in that beloved birth-land of Annan: Babylon, with its deafening inanity rages on; but to him henceforth innocuous, unheeded—for ever." Such is the great personality who, for a few years, glorified this humble street in the Calton. Now sub-divided into one and two-apartment houses, we devoutly inspected them all as having sheltered one of the mighty ones of the earth ninety-five years ago.

Entering Moncur Street, we stand for a few minutes to take a look at the Calton Entry from Gallowgate Street. This was the west boundary line of the old burgh. The whitewashed walls, the red-tlled roofs, and the topsy-turvy style of buildings are indicative of the early days when each proprietor was a " law unto himself," when Deans of Guild were unknown, and a systematic irregularity was the inevitable result. One sometimes wonders if the long line of straight frontages, which is now the vogue in our modern towns—miles and miles of dreary two and three-storey buildings, not in any way distinguishable from one another, except by the number placed above the door—is any real improvement upon the higgledy-piggledy system of our forefathers. The monotony of our present system—the long line of sameness without a break, the want of an original idea, the utter absence of individual imagination either in architecture or internal design, are very questionable indications of progress, and rather point to a struggle to observe the terms of the Building Acts and at the same time to make the building of houses a paying speculation. No high thoughts nor lofty aspirations can be engendered by our present system of town architecture.

At the south-west corner of the children's playground in Bain Square, we look across the Gallowgate to the steeple of St. John's Parish Church, where Dr. Thomas Chalmers spent so many years of a noble life until he was translated to Edinburgh. The playground is a very small one, occupying the square which was formed here and named after Sir James Bain, who was Lord Provost in 1874. It is opposite St. Luke's Parish Church, and is very popular with the children. The popularity of a playground is greatly increased by the attention and sympathy of its guardian. In " Old Bob ' we have one of that human rara avis who combines thc sympathy and the firmness which are so necessary in all those who have to do with the young. He does his lowly but useful work well.

Before inspecting the Corporation balcony blocks entered from 5 King Street, at the north end of the square, we take a look eastwards along this street (known in the old days as Beggars' Row). It extends its irregular course the whole length of the northern part of the Calton, until it reaches Abercromby Street, changing its name at the eastern end into Millroad Street. I have no doubt that at some future period it will be reconstructed into a broad and elegant boulevard to relieve part of the congestion in Gallowgate from Abercromby Street to Bain Square, and then the last remnants will disappear, which still earns for it the sinister sobriquet of The Beggars' Row."

The most modern Corporation working-men's dwellings are in Moncur Street. When erected twenty or thirty years ago they were considered the best class of house for our working classes. Built round an internal court, they are four-flatted brick buildings containing two-apartment houses, approached by tower-looking staircases giving access to overhung balconies, from which the kitchens of the respective dwellings are immediately entered. In adopting this style of building, the Improvement Trust followed the example of the Glasgow Workmen's Dwellings Company, who, after considerable opposition in the Dean of Guild Court, erected in 1892 their well-known five-storey balcony blocks in Cathedral Court, entered from the Rottenrow. Some things can be said in favour of the " balcony " system, and some things against it. There are certain disadvantages, namely, the deep shadows which are caused by such high buildings, and also by the balconies shutting out the sunlight from many of the houses, and in the dull days of our winter, causing extra expense for gas in the lower-flatted houses. Suffice it to say that such buildings would not now be accepted as offering a reasonable or desirable solution of one of the most urgent social problems which the nation will have to face when the war is over.

Turning round into Moncur Street, we note at the corner, on the north side, the building occupied by the Glasgow Medical Mission, where the bodily ailments of our poorer classes receive expert attention free of charge.

Before proceeding down Main Street to Kirk Street, we pause to inspect the latest effort of the Improvement Trust to meet the needs of the poor for houses at the lowest rents. It is a definite departure from their King Street buildings. The limit of height is three flats, and the balconies are abolished. The houses are of the one and two-apartment order, fortyeight of them being what are termed " farmed-out houses." The Corporation were urged by the Municipal Housing Commission In 1904 to make an experiment in housing a class of poor people who had, through one cause or another, or a combination of causes, lost their furniture. These unfortunates fell into the hands of small capitalists of their own class, who, as a rule, " took them in " in more senses than one. Of all the classes who still are able to pay enough weekly for the sole use of a furnished apartment, they are the lowest, and perhaps the most refractory. An infatuation for drink on the part of the husband or of the wife, and sometimes of both, is the main cause of their fall, and so they have to pay 5s. per week for their single apartment, instead of 4s. 4d., or £l 14s. 8d. per annum for the use of furniture, the total value of which very rarely exceeds the sum of thirty shillings. Time alone will show the usefulness of this experiment. Its main value will probably consist in the opportunities it will afford of setting these people once more on the path of sober and respectable citizenship. If it cannot do this, it will fail.

Walking past the old Calton Cross and going a short distance down Well Street, we step in to have a look at the interior of this building which, for many years, was used by the management of the Glasgow and West of Scotland Technical College as a weaving school. The place is now loomless, and the shuttles dart to and fro in it no more. But its power for good is still felt throughout the world. Some few years ago I had a visit from an old friend who was one of its eager students. He carried the knowledge acquired there to the United States of America, and by weaving in that country has amassed a huge fortune. Nimble fingers within are now working at a product of a different kind. Cloth has given place to chocolates, the loom to the moulding table and the roller, and the weft and woof to sugar and the substance of the cocoa-bean. It is from this place that Mr. Agnew is trying to sweeten the world, and to all appearances doing it successfully. It was a pleasing sight which met our eyes as we went through the different departments— the cleanly, healthy, and bright appearance of the girls, all suitably arrayed for their work, from the mixing and moulding to the final packing.

The U.F. Church in Kirk Street, like its sister church in Tobago Street, which we come to later on, has no conspicuous outward symbols of distinction and grandeur. But although externally plain and unadorned, it seems, through the years, to have engendered memories of happiness and grace far outweighing the pleasures of the eye. One of its past ministers, the Reverend Robert Campbell, put his experience of it in a little poem of seven verses, two of which I will recite. He says—

“O dear, dear kirk in Kirk Street, thou hast neither tower nor spire,

“Nor pealing wind-swept organ inspiring church and choir,

“Nor beauteous stained-glass windows, with their soft “religious light,

“Memorials of the sainted, who have passed away from sight.

"But thy very walls are holy, and the dust which time has made,

“Where the mighty Harvie thundered, and the gentle Stewart prayed,

“Where many a weary sinner has thrown away his load,

And rays from the eternal cheered the seeker after God."

I doubt not that many can vouch for the truth and sincerity of these heart-felt words.

The court behind No. 16, with its back lands swiftly going to decay, is a real bit of old Calton. Walking through this court, we emerge again in Moncur Street, and if it is Saturday, we gaze upon a busy scene. The vacant ground across the street has been leased temporarily to two parties, who sub-let stances to those who own or hire barrows, upon which are displayed all kinds of merchandise, from old locks and keys to floorcloth and linoleum of all sizes and patterns, the stances (ranging from 400 to 500) cost 6d. to 9d. per barrow. To wander from barrow to barrow, to listen to the bargaining between buyers and sellers, and to observe the departure of the purchasers with their bargains is a liberal education in low commerce. Each stance-holder clears about one pound sterling as the result of the day's transactions. The larger articles are often disposed of by what is called the " Dutch Auction." That is, the owner of the barrow, not being a licensed auctioneer, holds up the article to be sold, and naming a maximum price for it, proceeds, with much circumlocutory speech as to its virtues and value, to descend in his figure step by step, until he has tempted one of his audience to become the purchaser. Where all this heterogeneous mass of clothing, clocks, watches, hats, umbrellas, parasols, rugs, metal, pictures, books, and other things too numerous to mention, have come from, is one of the mysteries of city life.

We now make our way down Green Street, one of the typical thoroughfares of the ancient burgh, towards the Day Industrial School. Part of this school, once known as the Lancastrian School, was used by the magistrates of Calton as their Small Debt Court. To-day, after alteration and expansion, it affords accommodation for 300 children. It may be called a gigantic creche, the pupils being the children of parents who work out all day. They get breakfast, dinner and tea in the institution, one shilling per child per week being the ordinary charge.

A short walk from Green Street takes us into Great Hamilton Street, which was opened for traffic in 1813, and named after John Hamilton, the chief magistrate of the Calton at that period. Before this time it was a mere footpath, named " The Pleasants," rising from its western end to an elevation about 15 feet in height at the eastern extremity. We soon reach Tobago Street (almost universally called " Tobacco Street " in this neighbourhood), where we find the Calton Parish Church, built in 1793 as a Chapel-of-Ease to the Barony Church.

Passing into Stevenson Street, originally known as Crossloan Street, but renamed after the second and greatest of the old burgh's provosts, Nathaniel Stevenson of Braidwood, we look westwards. The old burgh building or town hall faces us on the right, where the old Council deliberated and passed many of their antiquated regulations against beggars, strolling Sunday topers, and bad boys, such as Johnnie Johnstone, who was fined 2s. 6d. in 1822 for whistling in the street on the Sabbath day. Turning up Struthers Street, we get into what was the very centre of the handloom weaving area. Two relics of this once important industry remain in the Calton - one at 34 Struthers Street, and the other round the corner, in Bell Street. Mr. and Mrs. M' Laughlan, who live in Struthers Street, work at pattern weaving in pieces varying in length from five to forty yards. The short pieces can be done more cheaply in the hand-loom than by the power-loom. The designs are supplied by the warehouse customers, and the prices vary from 61/2 to 7d. per yard. This price has hardly varied during the past thirty years. A good weaver on the hand-loom can do about eight yards per day. Round the corner, in Bell Street, resides the only hand-loom weaver left in Calton, John M'Dowall, now over eighty years of age. He began weaving when he was ten years of age, and remembers the time when there were as many as thirty-four weaving shops in Bell Street. John does not do pattern weaving, but takes orders for petticoats, aprons, and such like, while his niece keeps filling the pirns for him on her spinning wheel.

Going south, down Bell Street, we again arrive at Stevenson Street, and look in at No. 74, where there is a back-land row of dwellings, running transversely from the line of the street, in which, twenty or thirty years ago, many of the old citizens of the Calton found quiet residence in clean and well-kept houses, the windows of which faced good greens and leafy trees. To-day a change has come over the scene. The houses are, for want of upkeep and repair, getting into their last stage as human dwellings, being let as farmed-out apartments at 5s. per week. There are 379 houses of this low class in the Calton ward, mostly occupied by those who, through indulgence in strong drink, have “melted" their furniture in the pawnshop.

A few steps eastward takes us to the boundary of the northern part of the ward, Abercromby Street, and as we proceed south to Canning Street we pass the great common lodging-house for men, owned by the Corporation. Abercromby Street was opened in 1802, and named in honour of Sir Ralph Abercromby, who, in 1801, was sent as commander-chief of the British army to dispossess the French from the land of the Pharaohs. In the hour of victory he was struck by a spent ball, and died seven days thereafter. When we reach the foot of John Street from Canning Street by way of Landressy Street, we are at the turning point of our tour.

Only the briefest reference can be made to the Logan and Johnston Institute, facing the Green, at the bottom of James Street. This "college of domesticity" trains our girls in all these homely arts which make good mothers and educated and self-reliant housekeepers. The Buchanan Institute, a few yards farther west, was founded by James Buchanan, who left £30,000 for the care and education of fatherless boys. The mansion has been greatly extended in recent years, and under the energetic superintendent, Mr. McLaren, 340 boys are daily fed, schooled, disciplined, and trained in various crafts, and fitted to take their place in the service of the empire, either at home or in the colonies. The institute faces the "People's Park," a place which would require a separate lecture to do justice to its historic points and its value to the community.